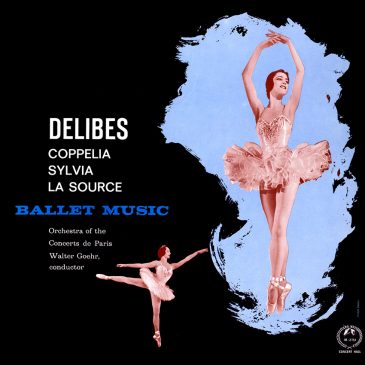

Delibes, Orchestra Of The Concerts De Paris, Walter Goehr – Ballet Music

Sleeve Notes: If ever you are haunted by an attractive, piquant tune which you cannot place—probably nineteenth-century French, too light-fingered for Gounod, not individual enough for Bizet or Massenet, yet far more so than Saint-Sans—you may be fairly certain that … Continued