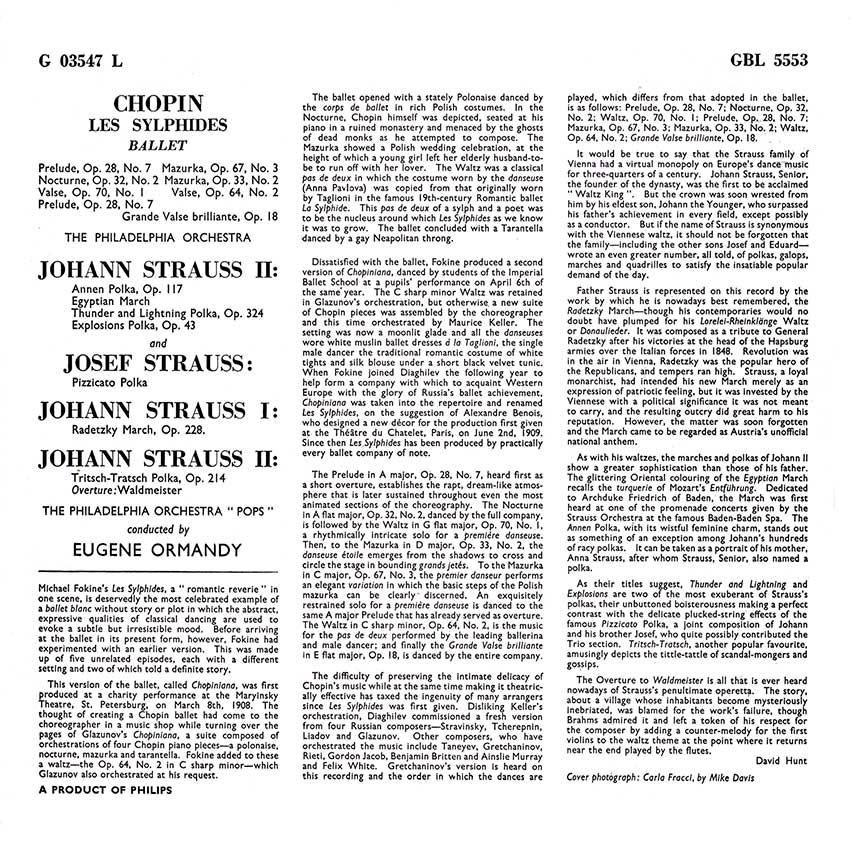

Sleeve Notes:

Michael Fokine’s Les Sylphides, a ” romantic reverie ” in one scene, is deservedly the most celebrated example of a ballet blanc without story or plot in which the abstract, expressive qualities of classical dancing are used to evoke a subtle but irresistible mood. Before arriving at the ballet in its present form, however, Fokine had experimented with an earlier version. This was made up of five unrelated episodes, each with a different setting and two of which told a definite story.

The ballet opened with a stately Polonaise danced by the corps de ballet in rich Polish costumes. In the Nocturne, Chopin himself was depicted, seated at his piano in a ruined monastery and menaced by the ghosts of dead monks as he attempted to compose. The Mazurka showed a Polish wedding celebration, at the height of which a young girl left her elderly husband-to-be to run off with her lover. The Waltz was a classical pas de deux in which the costume worn by the danseuse (Anna Pavlova) was copied from that originally worn by Taglioni in the famous 19th-century Romantic ballet La Sylphide. This pas de deux of a sylph and a poet was to be the nucleus around which Les Sylphides as we know it was to grow. The ballet concluded with a Tarantella danced by a gay Neapolitan throng.

Dissatisfied with the ballet, Fokine produced a second version of Chopiniana, danced by students of the Imperial Ballet School at a pupils’ performance on April 6th of the same’ year. The C sharp minor Waltz was retained in Glazunov’s orchestration, but otherwise. a new suite of Chopin pieces was assembled by the choreographer and this time orchestrated by Maurice Keller. The setting was now a moonlit glade and all the danseuses wore white muslin ballet dresses á la Taglioni, the single male dancer the traditional romantic costume of white tights and silk blouse under a short black velvet tunic. When Fokine joined Diaghilev the following year to help form a company with which to acquaint Western Europe with the glory of Russia’s ballet achievement, Chopiniana was taken into the repertoire and renamed Les Sylphides, on the suggestion of Alexandre Benois, who designed a new decor for the production first given at the Theatre du Chatelet, Paris, on June 2nd, 1909. Since then Les Sylphides has been produced by practically every ballet company of note.

The Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7, heard first as a short overture, establishes the rapt, dream-like atmosphere that is later sustained throughout even the most animated sections of the choreography. The Nocturne in A flat major, Op. 32, No. 2, danced by the full company, is followed by the Waltz in G flat major, Op. 70, No. I, a rhythmically intricate solo for a premiere danseuse. Then, to the Mazurka in D major, Op. 33, No. 2, the danseuse Rolle emerges from the shadows to cross and circle the stage in bounding grands jetes. To the Mazurka in C major, Op. 67, No. 3, the premier danseur performs an elegant variation In which the basic steps of the Polish mazurka can be clearly’ discerned. An exquisitely restrained solo for a premiere danseuse is danced to the same A major Prelude that has already served as overture. The Waltz in C sharp minor, Op. 64, No. 2, is the music for the pas de deux performed by the leading ballerina and male dancer; and finally the Grande Valse brilliante in E flat major, Op. 18, is danced by the entire company.

The difficulty of preserving the Intimate delicacy of Chopin’s music while at the same time making it theatrically effective has taxed the ingenuity of many arrangers since Les Sylphides was first given. Disliking Keller’s orchestration, Diaghilev commissioned a fresh version from four Russian composers—Stravinsky, Tcherepnin, Lladov and Glazunov. Other composers, who have orchestrated the music include Taneyev, Gretchaninov, Rieti, Gordon Jacob, Benjamin Britten and Ainslie Murray and Felix White. Gretchaninov’s version Is heard on this recording and the order in which the dances are played, which differs from that adopted in the ballet, is as follows: Prelude, Op. 28, No. 7; Nocturne, Op. 32, No. 2; Waltz, Op. 70, No. I; Prelude, Op. 28, No. 7; Mazurka, Op. 67, No. 3; Mazurka, Op. 33, No. 2; Waltz, Op. 64, No. 2; Grande Valse brillionte, Op. 18.

dance music for three-quarters of a century. Johann Strauss, Senior, the founder of the dynasty, was the first to be acclaimed ” Waltz King “. But the crown was soon wrested from him by his eldest son, Johann the Younger, who surpassed his father’s achievement in every field, except possibly as a conductor. But if the name of Strauss is synonymous with the Viennese waltz, it should not be forgotten that the family—including the other sons Josef and Eduard—wrote an even greater number, all told, of polkas, galops, marches and quadrilles to satisfy the insatiable popular demand of the day.

Father Strauss is represented on this record by the work by which he is nowadays best remembered, the Radetzky March—though his contemporaries would no doubt have plumped for his Lorelel-Rheinkldnge Waltz or Donaulieder. It was composed as a tribute to General Radetzky after his victories at the head of the Hapsburg armies over the Italian forces in 1848. Revolution was in the air in Vienna, Radetzky was the popular hero of the Republicans, and tempers ran high. Strauss, a loyal monarchist, had intended his new March merely as an expression of patriotic feeling, but it was invested by the Viennese with a political significance it was not meant to carry, and the resulting outcry did great harm to his reputation. However, the matter was soon forgotten and the March came to be regarded as Austria’s unofficial national anthem.

As with his waltzes, the marches and polkas of Johann II show a greater sophistication than those of his father. The glittering Oriental colouring of the Egyptian March recalls the turquerie of Mozart’s Entfuhrung. Dedicated to Archduke Friedrich of Baden, the March was first heard at one of the promenade concerts given by the Strauss Orchestra at the famous Baden-Baden Spa. The Annen Polka, with its wistful feminine charm, stands out as something of an exception among Johann’s hundreds of racy polkas. It can be taken as a portrait of his mother, Anna Strauss, after whom Strauss, Senior, also named a polka.

As their titles suggest, Thunder and Lightning and Explosions are two of the most exuberant of Strauss’s polkas, their unbuttoned boisterousness making a perfect contrast with the delicate plucked-string effects of the famous Pizzicato Polka, a joint composition of Johann and his brother Josef, who quite possibly contributed the Trio section. Tritsch-Trotsch, another popular favourite, amusingly depicts the tittle-tattle of scandal-mongers and gossips. The Overture to Waldmeister is all that is ever heard nowadays of Strauss’s penultimate operetta. The story, about a village whose inhabitants become mysteriously Inebriated, was blamed for the work’s failure, though Brahms admired it and left a token of his respect for the composer by adding a counter-melody for the first violins to the waltz theme at the point where It returns near the end played by the flutes.

David Hunt

Label: Philips GL 03547 L

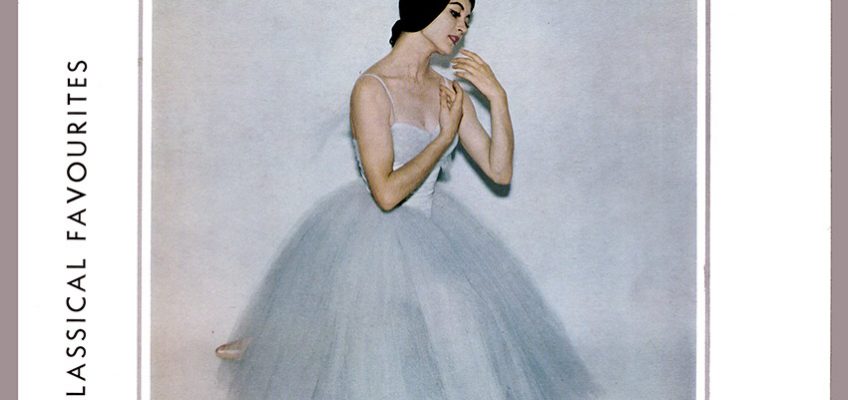

Cover photograph: Carla Fracci, by Mike Davis