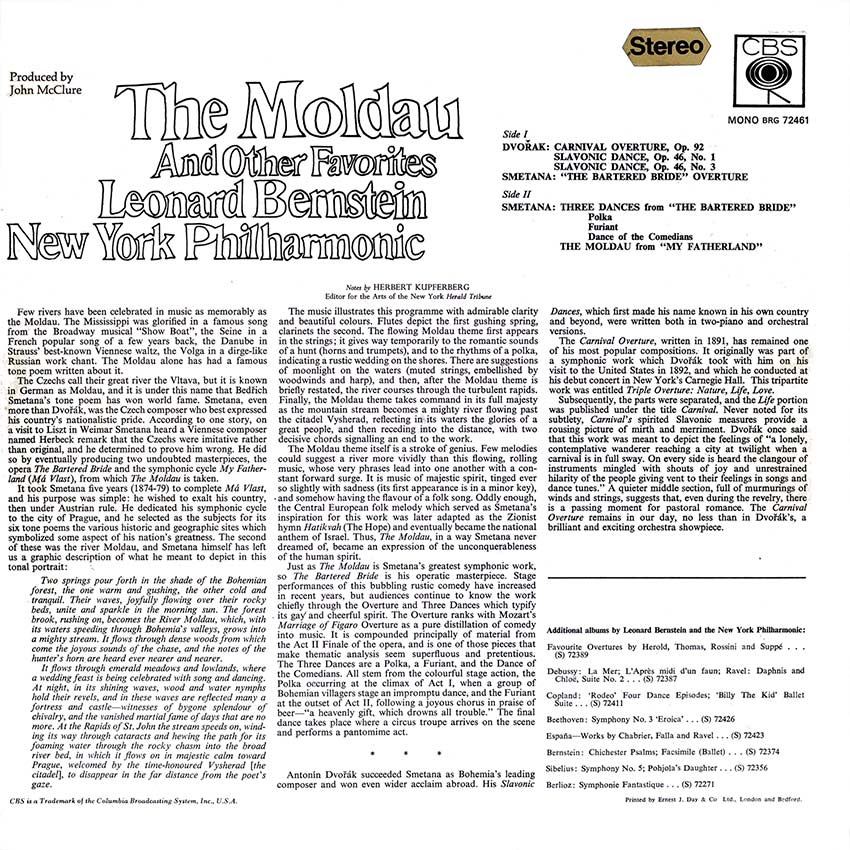

Sleeve Notes:

Notes by HERBERT KUPFERBERG Editor for the Arts of the New York Herald Tribune

Few rivers have been celebrated in music as memorably as the Moldau. The Mississippi was glorified in a famous song from the Broadway musical “Show Boat”, the Seine in a French popular song of a few years back, the Danube in Strauss’ best-known Viennese waltz, the Volga in a dirge-like Russian work chant. The Moldau alone has had a famous tone poem written about it.

It took Smetana five years (1874-79) to complete Má Vlast, and his purpose was simple: he wished to exalt his country, then under Austrian rule. He dedicated his symphonic cycle to the city of Prague, and he selected as the subjects for its six tone poems the various historic and geographic sites which symbolized some aspect of his nation’s greatness. The second of these was the river Moldau, and Smetana himself has left us a graphic description of what he meant to depict in this tonal portrait:

Two springs pour forth in the shade of the Bohemian forest, the one warm and gushing, the other cold and tranquil. Their waves, joyfully flowing over their rocky beds, unite and sparkle in the morning sun. The forest brook, rushing on, becomes the River Moldau, which, with its waters speeding through Bohemia’s valleys, grows into a mighty stream. It flows through dense woods from which come the joyous sounds of the chase, and the notes of the hunter’s horn are heard ever nearer and nearer.

It flows through emerald meadows and lowlands, where a wedding feast is being celebrated with song and dancing. At night, in its shining waves, wood and water nymphs hold their revels, and in these waves are reflected many a fortress and castle—witnesses of bygone splendour of chivalry, and the vanished martial fame of days that are no more. At the Rapids of St. John the stream speeds on, winding its way through cataracts and hewing the path for its foaming water through the rocky chasm into the broad river bed, in which it flows on in majestic calm toward Prague, welcomed by the time-honoured Vysherad [the citadel], to disappear in the far distance from the poet’s gaze.

The music illustrates this programme with admirable clarity and beautiful colours. Flutes depict the first gushing spring, clarinets the second. The flowing Moldau theme first appears in the strings; it gives way temporarily to the romantic sounds of a hunt (horns and trumpets), and to the rhythms of a polka, indicating a rustic wedding on the shores. There are suggestions of moonlight on the waters (muted strings, embellished by woodwinds and harp), and then, after the Moldau theme is briefly restated, the river courses through the turbulent rapids. Finally, the Moldau theme takes command in its full majesty as the mountain stream becomes a mighty river flowing past the citadel Vysherad, reflecting in its waters the glories of a great people, and then receding into the distance, with two decisive chords signalling an end to the work.

The Moldau theme itself is a stroke of genius. Few melodies could suggest a river more vividly than this flowing, rolling music, whose very phrases lead into one another with a constant forward surge. It is music of majestic spirit, tinged ever so slightly with sadness (its first appearance is in a minor key), and somehow having the flavour of a folk song. Oddly enough, the Central European folk melody which served as Smetana’s inspiration for this work was later adapted as the Zionist hymn Hatikvah (The Hope) and eventually became the national anthem of Israel. Thus, The Moldau, in a way Smetana never dreamed of, became an expression of the unconquerableness of the human spirit.

Just as The Moldau is Smetana’s greatest symphonic work, so The Bartered Bride is his operatic masterpiece. Stage performances of this bubbling rustic comedy have increased in recent years, but audiences continue to know the work chiefly through the Overture and Three Dances which typify its gay’ and cheerful spirit. The Overture ranks with Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro Overture as a pure distillation of comedy into music. It is compounded principally of material from the Act II Finale of the opera, and is one of those pieces that make thematic analysis seem superfluous and pretentious. The Three Dances are a Polka, a Furiant, and the Dance of the Comedians. All stem from the colourful stage action, the Polka occurring at the climax of Act I, when a group of Bohemian villagers stage an impromptu dance, and the Furiant at the outset of Act II, following a joyous chorus in praise of beer – “a heavenly gift, which drowns all trouble.” The final dance takes place where a circus troupe arrives on the scene and performs a pantomime act.

Antonin Dvořák succeeded Smetana as Bohemia’s leading composer and won even wider acclaim abroad. His Slavonic Dances, which first made his name known in his own country and beyond, were written both in two-piano and orchestral versions.

The Carnival Overture, written in 1891, has remained one of his most popular compositions. It originally was part of a symphonic work which Dvořák took with him on his visit to the United States in 1892, and which he conducted at his debut concert in New York’s Carnegie Hall. This tripartite work was entitled Triple Overture: Nature, Life, Love.

Subsequently, the parts were separated, and the Life portion was published under the title Carnival. Never noted for its subtlety, Carnival’s spirited Slavonic measures provide a rousing picture of mirth and merriment. Dvořák once said that this work was meant to depict the feelings of “a lonely, contemplative wanderer reaching a city at twilight when a carnival is in full sway. On every side is heard the clangour of instruments mingled with shouts of joy and unrestrained hilarity of the people giving vent to their feelings in songs and dance tunes.” A quieter middle section, full of murmurings of winds and strings, suggests that, even during the revelry, there is a passing moment for pastoral romance. The Carnival Overture remains in our day, no less than in Dvořák’s, a brilliant and exciting orchestra showpiece.

Label: CBS 72461