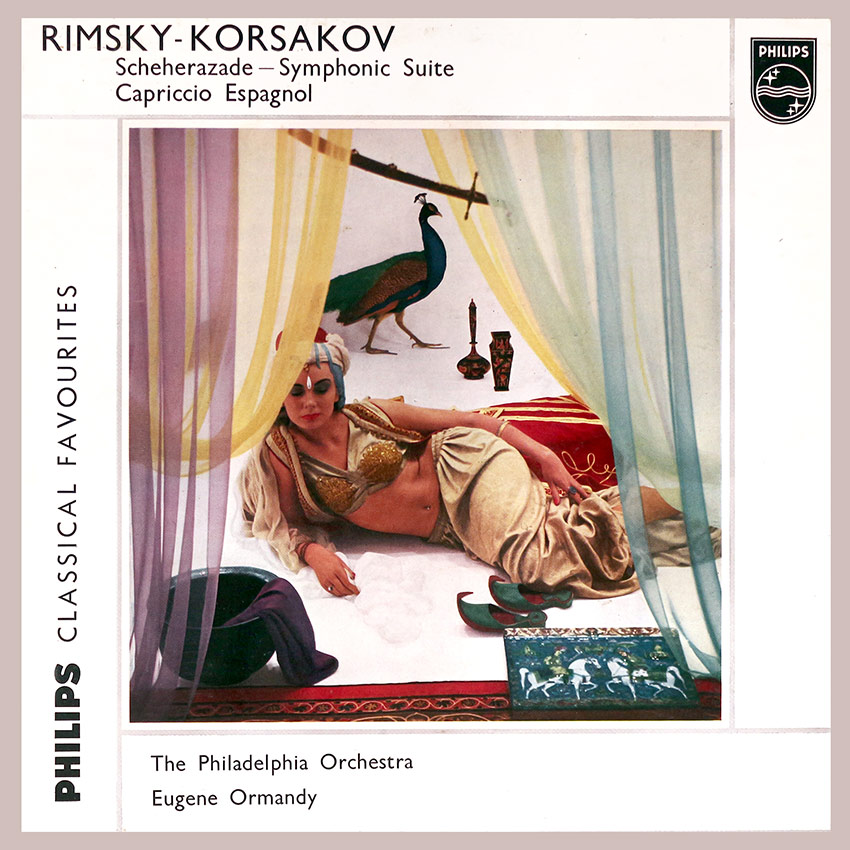

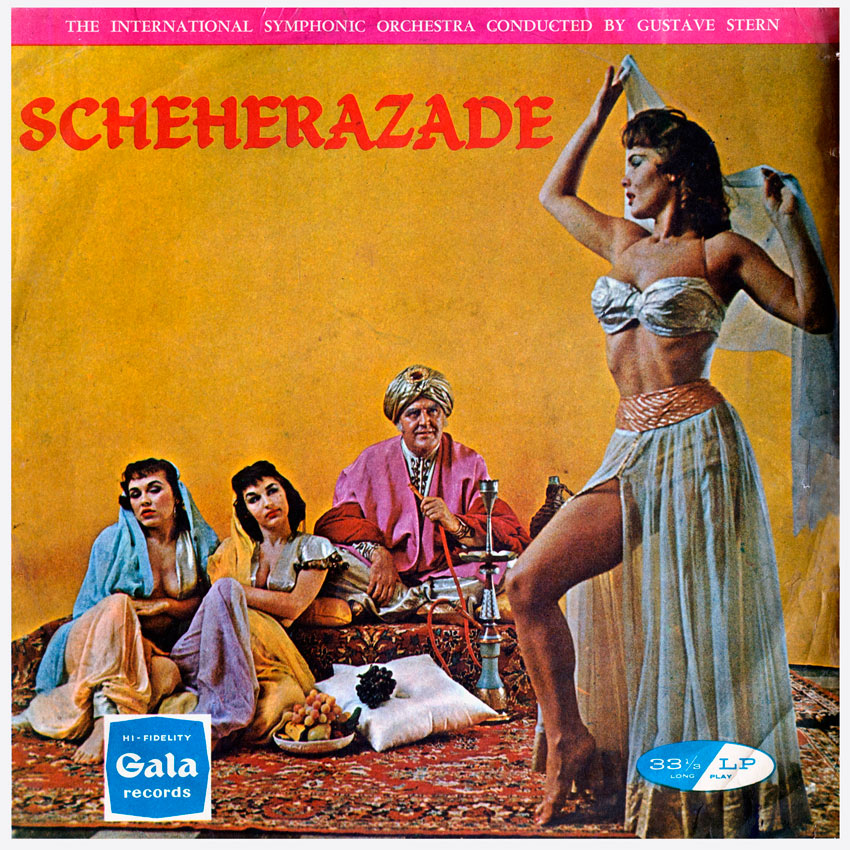

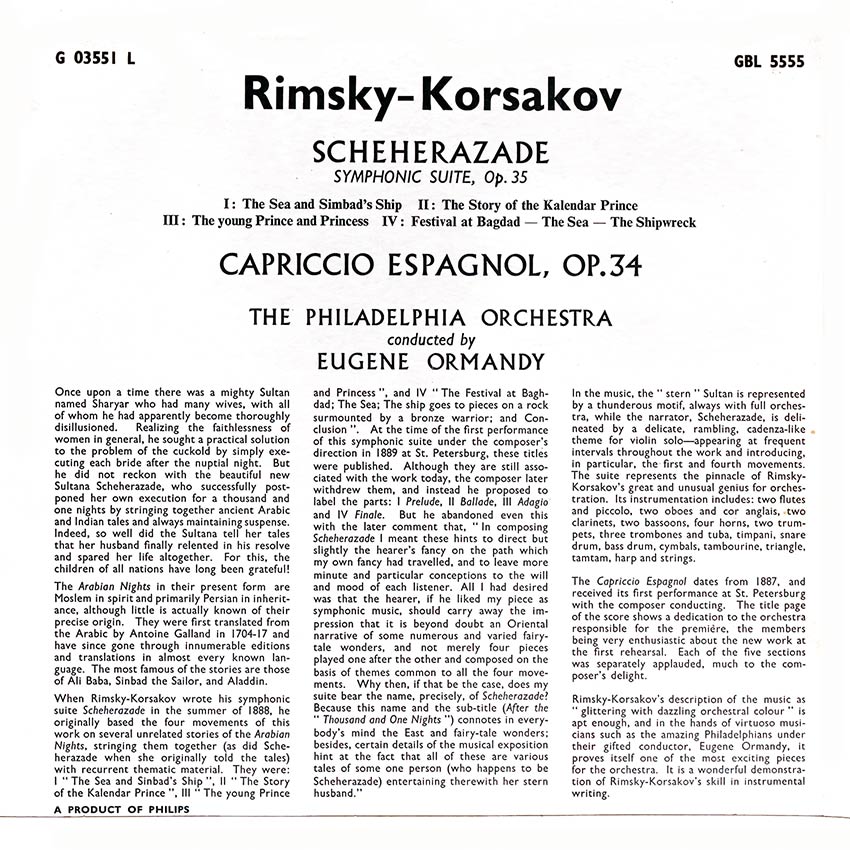

Philadelphia Orchestra – Rimsky-Korsakov – Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite/Capriccio Espagnol

Sleeve Notes:

Once upon a time there was a mighty Sultan named Sharyar who had many wives, with all of whom he had apparently become thoroughly disillusioned. Realizing the faithlessness of women in general, he sought a practical solution to the problem of the cuckold by simply executing each bride after the nuptial night.

The Arabian Nights In their present form are Moslem in spirit and primarily Persian in inheritance, although little is actually known of their precise origin. They were first translated from the Arabic by Antoine Galland in 1704-17 and have since gone through innumerable editions and translations in almost every known language. The most famous of the stories are those of All Baba, Sinbad the Sailor, and Aladdin.

When Rimsky-Korsakov wrote his symphonic suite Scheherazade in the summer of 1888, he originally based the four movements of this work on several unrelated stories of the Arabian Nights, stringing them together (as did Scheherazade when she originally told the tales) with recurrent thematic material. They were: ” The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship “, II ” The Story of the Kalendar Prince “, Ill ” The young Prince and Princess “, and IV ” The Festival at Bagh-dad; The Sea; The ship goes to pieces on a rock surmounted by a bronze warrior; and Conclusion “. At the time of the first performance of this symphonic suite under the composer’s direction in 1889 at St. Petersburg, these titles were published. Although they are still associated with the work today, the composer later withdrew them, and instead he proposed to label the parts: I Prelude, II Ballade, Ill Adagio and IV Finale. But he abandoned even this with the later comment that, ” In composing Scheherazade I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had travelled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions to the will and mood of each listener. All I had desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders, and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements. Why then, if that be the case, does my suite bear the name, precisely, of Scheherazade? Because this name and the sub-title (After the ” Thousand and One Nights”) connotes in every-body’s mind the East and fairy-tale wonders; besides, certain details of the musical exposition hint at the fact that all of these are various tales of some one person (who happens to be Scheherazade) entertaining therewith her stern husband.”

In the music, the ” stern ” Sultan is represented by a thunderous motif, always with full orchestra, while the narrator, Scheherazade, is delineated by a delicate, rambling, cadenza-like theme for violin solo—appearing at frequent intervals throughout the work and introducing, in particular, the first and fourth movements. The suite represents the pinnacle of Rimsky-Korsakov’s great and unusual genius for orchestration. Its instrumentation includes: two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and cor anglais, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, tamtam, harp and strings.

The Capriccio Espagnol dates from 1887, and received its first performance at St. Petersburg with the composer conducting. The title page of the score shows a dedication to the orchestra responsible for the premiere, the members being very enthusiastic about the new work at the first rehearsal. Each of the five sections was separately applauded, much to the com-poser’s delight.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s description of the music as ” glittering with dazzling orchestral colour ” is apt enough, and in the hands of virtuoso musicians such as the amazing Philadelphians under their gifted conductor, Eugene Ormandy, it proves itself one of the most exciting pieces for the orchestra. It is a wonderful demonstration of Rimsky-Korsakov’s skill in instrumental writing.

The Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy

Label: Philips GBL 5555