It is quite fashionable, in certain circles, to look down a long and highly patronizing nose at Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, to dismiss his music as overblown and over-emotional, and in general to rank his creative genius low down on the compositorial totem pole. Poor Tchaikovsky. It was no better during his lifetime when, even at the height of his international fame. he had to dodge all manner of critical brickbats. The Fourth Symphony, according to one of his learned contemporaries, is “confusion, twaddle and tittle-tattle”: the Fifth, in case you never noticed, “sounds like a horde of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy”: the Pathetique “threads all the foul ditches and sewers, as vulgar, obscene and unclean as music can be.” “Absolutely the most hideous thing ever put on paper” was a Boston critic ‘s tender appraisal of the “Marche Slave “, while in Vienna, the celebrated Eduard Hanslick stoutly maintained that no, the Violin Concerto earned that distinction. “It gives us for the first time”, Hanslick observed. “the monstrous notion that there can be music that stinks to the ear.”

What, then, accounts for the fact that Tchaikovsky is as popular with the average concert-goer as he is unpopular with the cognoscenti? Why are his concertos and symphonies loved better and played more frequently that those of almost anyone except Beethoven himself?

Why, if it comes to that, does his music repeatedly attracted the kleptomaniacal attention of pop hit-makers on Broadway and Tin Pan Alley? Two full-scale musical comedies were based on Tchaikovsky’s composition, and at least half a dozen Hit Parade tunes were blithely lifted from his classical pages. “Tonight We Love” (otherwise known as the Piano Concerto No.1.) is probably the best known of these, but not too far behind in popularity came “The Story of a Starry Night” (from the Sixth Symphony), the equally celestial “Moon Love” (from the Fifth), “On the Isle of May” (Andante Cantabile), “Our Love.. (Romeo and Juliet) and “The Things I Love” (Romance in F Minor).

We are not going to come up with a nice, neat explanation for this phenomenon, of course, but it seems likely that beyond the obvious reasons Tchaikovsky’s glowing gift for melody, his instinctive feeling for instrumental colors, and so on lies his conception of music as a grand and glorious emotional explosion. He admitted that he would probably go to his grave without ever being able to compose a piece in perfect form, but he exulted in his ability to let music speak from and to the heart, rather than the intellect. “Composing”, he confided to his benefactress Mme. von Meek “is a purely lyrical process, a sort of confession of the soul in music, an accumulation of material flowing forth in notes, just as the lyric poet pours himself out in verse.” Here then would seem to be at least part of the secret of Tchaikovsky’s communicative success: his music is frankly. openly, unabashedly emotional, and it touches us accordingly.

Tchaikovsky’s personal life was a morass of fears, psychoses and traumas. “He was as brittle as porcelain”, his governess wrote about the boy, then aged five or six: “a trifle wounded him deeply, and the least criticism or reproof would upset him alarmingly. I also observed that music had a great effect upon his nervous system, and after a lesson, he was invariably overwrought and excited. Once I found him sitting up in bed with bright, feverish eyes, crying to himself. ‘Oh, this music, this music’, he said. ‘save me from it, it will not give me any peace.”

Nor was Tchaikovsky to find inner peace as he grew up. He remained moody, tense and inordinately shy: he added a collection of morbid fears and superstitions to his blossoming list of psychological ailments: and he soon became the proud possessor of the world’s most highly developed inferiority complex. He destroyed several operas and all manner of lesser pieces because he considered them unworthy, and even when his inspiration ran highest and public enthusiasm was at its peak, he tortured himself with totally unfounded fears that his creative powers had fled. He had several nervous breakdowns, attempted suicide (by standing up to his neck in the icy waters of the Neva River), and gave up conducting for a ten-year period because he was terrified that the exertion might make his head roll off his shoulders. “A worm continually gnaws in secret at my heart”, reads one entry in his diary: “the greater reason I have to be happy, the more discontented I become”

How fortunate for us all that Tchaikovsky never allowed the turmoil of his everyday affairs to interfere with his musical destiny. He worked steadily, in good times and bad, making notes in a little book he always carried with him (a la Beethoven), and carefully setting aside a specific number of hours every day for composition. When he became deeply involved with a particular piece, he would plunge into it, skipping meals and working right through sleepless nights. “It is the duty of an artist never to submit to laziness”, he wrote Mme. von Mack; “one cannot afford to sit and wait for inspiration she, a guest who comes only to those who call her.”

The divorce of his creative and personal lives was as complete as he could make it. We have an unequivocal statement from Tchaikovsky to the effect that the emotions expressed in his music did not well out of his frame of mind at the time of composition, but rather were always and invariably retrospective.”With no particular reasons for rejoicing.., he wrote. “I can experience a happy creative mood, and on the other hand, in the happiest of circumstance might write music filled with darkness an despair. The important thing is to rid oneself of the troubles of worldly existence, and to surrender oneself unconditionally to the artistic life.”

The fruits of this unconditional surrender comprise the immortal legacy of Peter Tchaikovsky the perennially popular ballets, the dramatic tone poems, the mighty symphonies, the beautiful operas, the scintillating concertos. What if his music does wear its heart on its sleeve? It’s a marvellously handsome sleeve and an ingratiatingly warm heart. Even the most familiar of his pieces never sound trite or shopworn their melodic freshness carries the day every time.

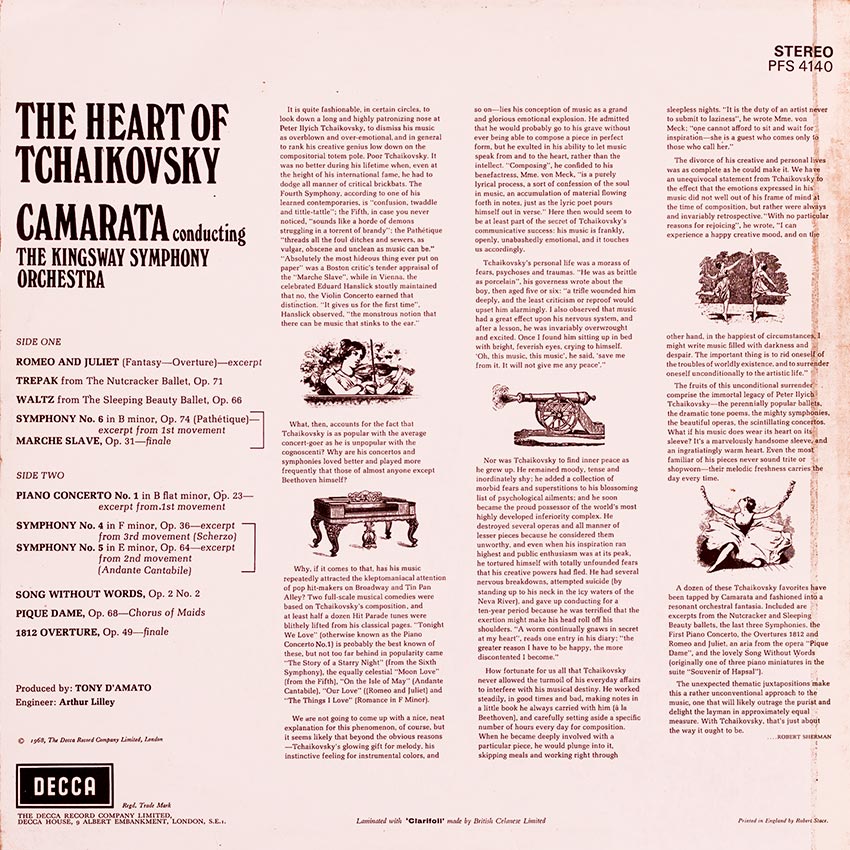

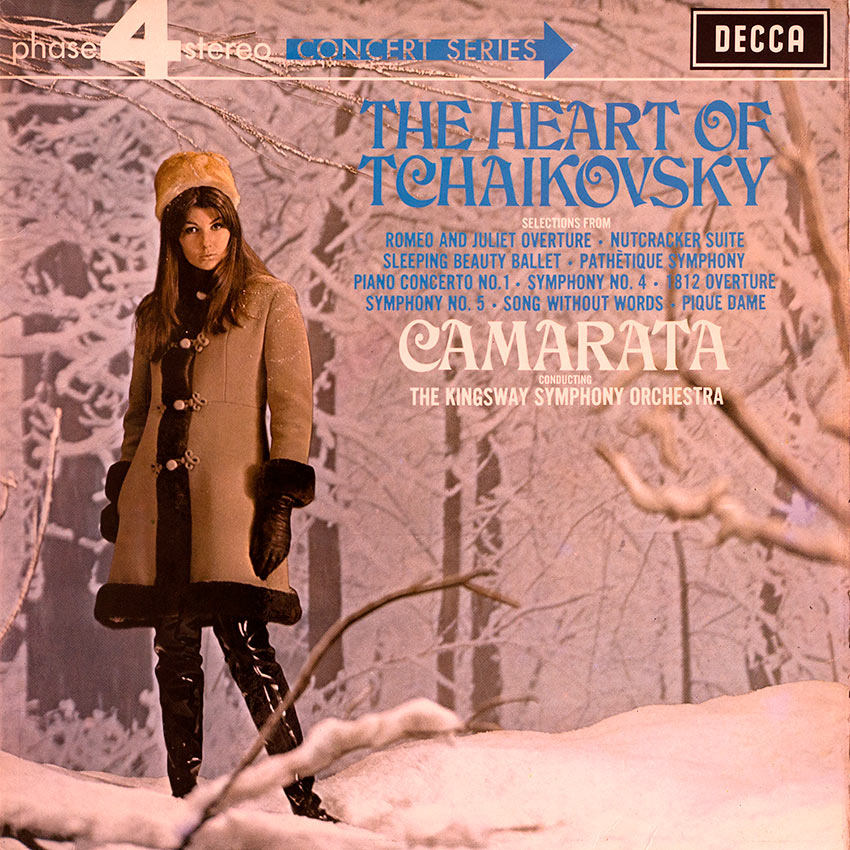

A dozen of these Tchaikovsky favorites have been tapped by Camarata and fashioned into a resonant orchestral fantasia. Included are excerpts from the Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty ballets, the last three Symphonies, the First Piano Concerto, the Overtures 1812 and Romeo and Juliet, an aria from the opera “Pique Dame”, and the lovely Song Without Words (originally one of three piano miniatures in the suite “Souvenir of Hapsal”).

The unexpected thematic juxtapositions make this a rather unconventional approach to the music, one that will likely outrage the purist end delight the layman in approximately equal measure. With Tchaikovsky, that’s just about the way it ought to be.

Robert Sherman