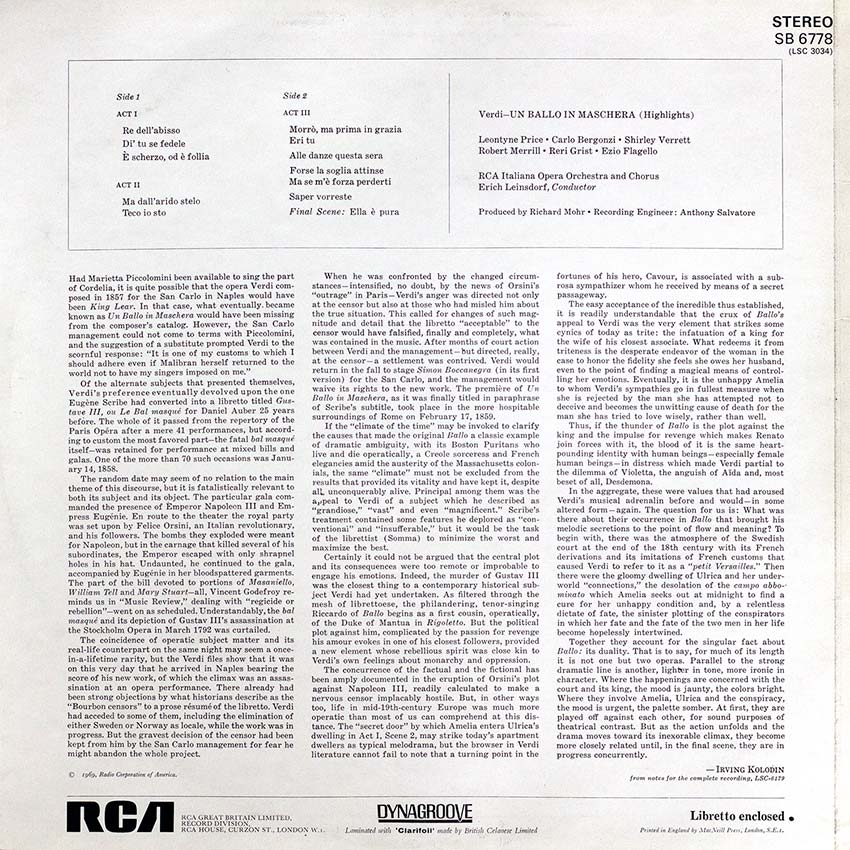

Sleeve Notes:

Had Marietta Piccolomini been available to sing the part of Cordelia, it is quite possible that the opera Verdi composed in 1857 for the San Carlo in Naples would have been King Lear. In that case, what eventually became known as Un Ballo in Maschera would have been missing from the composer’s catalog. However, the San Carlo management could not come to terms with Piccolomini, and the suggestion of a substitute prompted Verdi to the scornful response: “It is one of my customs to which I should adhere even if Malibran herself returned to the world not to have my singers imposed on me.”

The random date may seem of no relation to the main theme of this discourse, but it is fatalistically relevant to both its subject and its object. The particular gala commanded the presence of Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie. En route to the theater the royal party was set upon by Felice Orsini, an Italian revolutionary, and his followers. The bombs they exploded were meant for Napoleon, but in the carnage that killed several of his subordinates, the Emperor escaped with only shrapnel holes in his hat. Undaunted, he continued to the gala, accompanied by Eugenie in her bloodspattered garments. The part of the bill devoted to portions of Masaniello, William Tell and Mary Stuart – all, Vincent Godefroy reminds us in “Music Review,” dealing with “regicide or rebellion” – went on as scheduled. Understandably, the bal masque and its depiction of Gustav III’s assassination at the Stockholm Opera in March 1792 was curtailed.

The coincidence of operatic subject matter and its real-life counterpart on the same night may seem a once-in-a-lifetime rarity, but the Verdi files show that it was on this very day that he arrived in Naples bearing the score of his new work, of which the climax was an assassination at an opera performance. There already had been strong objections by what historians describe as the “Bourbon censors” to a prose résumé of the libretto. Verdi had acceded to some of them, including the elimination of either Sweden or Norway as locale, while the work was in progress. But the gravest decision of the censor had been kept from him by the San Carlo management for fear he might abandon the whole project.

When he was confronted by the changed circumstances – intensified, no doubt, by the news of Orsini’s “outrage” in Paris – Verdi’s anger was directed not only at the censor but also at those who had misled him about the true situation. This called for changes of such magnitude and detail that the libretto “acceptable” to the censor would have falsified, finally and completely, what was contained in the music. After months of court action between Verdi and the management—but directed, really, at the censor – a settlement was contrived. Verdi would return in the fall to stage Simon Boccanegra (in its first version) for the San Carlo, and the management would waive its rights to the new work. The premiere of Un Ballo in Maschera, as it was finally titled in paraphrase of Scribe’s subtitle, took place in the more hospitable surroundings of Rome on February 17, 1859.

If the “climate of the time” may be invoked to clarify the causes that made the original Ballo a classic example of dramatic ambiguity, with its Boston Puritans who live and die operatically, a Creole sorceress and French elegancies amid the austerity of the Massachusetts colonials, the same “climate” must not be excluded from the results that provided its vitality and have kept it, despite all., unconquerably alive. Principal among them was the appeal to Verdi of a subject which he described as “grandiose,” “vast” and even “magnificent.” Scribe’s treatment contained some features he deplored as “conventional” and “insufferable,” but it would be the task of the librettist (Somma) to minimize the worst and maximize the best.

Certainly it could not be argued that the central plot and its consequences were too remote or improbable to engage his emotions. Indeed, the murder of Gustav III was the closest thing to a contemporary historical subject Verdi had yet undertaken. As filtered through the mesh of librettoese, the philandering, tenor-singing Riccardo of Ballo begins as a first cousin, operatically, of the Duke of Mantua in Rigoletto. But the political plot against him, complicated by the passion for revenge his amour evokes in one of his closest followers, provided a new element whose rebellious spirit was close kin to Verdi’s own feelings about monarchy and oppression.

The concurrence of the factual and the fictional has been amply documented in the eruption of Orsini’s plot against Napoleon III, readily calculated to make a nervous censor implacably hostile. But, in other ways too, life in mid-19th-century Europe was much more operatic than most of us can comprehend at this distance. The “secret door” by which Amelia enters Ulrica’s dwelling in Act I, Scene 2, may strike today’s apartment dwellers as typical melodrama, but the browser in Verdi literature cannot fail to note that a turning point in the fortunes of his hero, Cavour, is associated with a sub-rosa sympathizer whom he received by means of a secret passageway.

The easy acceptance of the incredible thus established, it is readily understandable that the crux of Ballo’s appeal to Verdi was the very element that strikes some cynics of today as trite : the infatuation of a king for the wife of his closest associate. What redeems it from triteness is the desperate endeavor of the woman in the case to honor the fidelity she feels she owes her husband, even to the point of finding a magical means of control-ling her emotions. Eventually, it is the unhappy Amelia to whom Verdi’s sympathies go in fullest measure when she is rejected by the man she has attempted not to deceive and becomes the unwitting cause of death for the man she has tried to love wisely, rather than well.

Thus, if the thunder of Ballo is the plot against the king and the impulse for revenge which makes Renato join forces with it, the blood of it is the same heart-pounding identity with human beings – especially female human beings – in distress which made Verdi partial to the dilemma of Violetta, the anguish of Aida and, most beset of all, Desdemona.

In the aggregate, these were values that had aroused Verdi’s musical adrenalin before and would – in some altered form -again. The question for us is : What was there about their occurrence in Ballo that brought his melodic secretions to the point of flow and meaning? To begin with, there was the atmosphere of the Swedish court at the end of the 18th century with its French derivations and its imitations of French customs that caused Verdi to refer to it as a “petit Versailles.” Then there were the gloomy dwelling of Ulrica and her under-world “connections,” the desolation of the campo abbominato which Amelia seeks out at midnight to find a cure for her unhappy condition and, by a relentless dictate of fate, the sinister plotting of the conspirators in which her fate and the fate of the two men in her life become hopelessly intertwined.

Together they account for the singular fact about Ballo: its duality. That is to say, for much of its length it is not one but two operas. Parallel to the strong dramatic line is another, lighter in tone, more ironic in character. Where the happenings are concerned with the court and its king, the mood is jaunty, the colors bright. Where they involve Amelia, Ulrica and the conspiracy, the mood is urgent, the palette somber. At first, they are played off against each other, for sound purposes of theatrical contrast. But as the action unfolds and the drama moves toward its inexorable climax, they become more closely related until, in the final scene, they are in progress concurrently.

IRVING KOL015IN from notes for the complete recording, LSC-6179

Label: RCA Red Seal SB 6778