Sleeve Notes:

Few works in the entire literature of orchestral music can match Scheherazade for brilliance, appeal or vividness of instrumental coloring. But then, few composers have possessed the wizardry to orchestrate music as did Rimsky-Korsakov. And until now, it has been difficult to reproduce the full spectrum of the composer’s palette on records. Thanks to advanced recording techniques every subtle oriental shading, every overtone of this sumptuous symphonic suite can be enjoyed with startling realism in the home.

Rimsky-Korsakov composed Scheherazade during the summer of 1888, completing it early in August. It was first per-formed the following winter at the Russian Symphony Concerts in St. Petersburg.

Considering the opulence and infinite variety of sounds produced in this symphonic suite, the instrumental requirements of the score are relatively modest. They are: two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, kettledrums, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, triangle, tambourine, tam-tam, harp and strings. The work bears a dedication to the critic, Vladimir Stassov.

Prefacing the score of Scheherazade are the following introductory remarks, written by the composer:

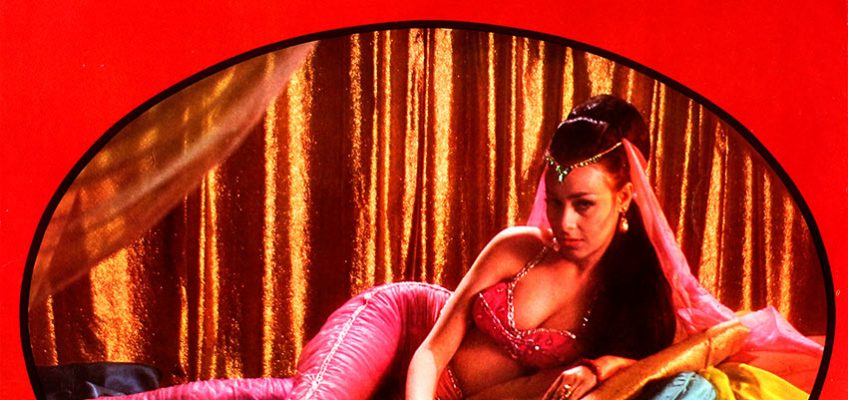

“The Sultan Schahriar, persuaded of the falseness and the faithlessness of women, has sworn to put to death each one of his wives after the first night. But the Sultana Scheherazade saved her life by interesting him in tales which she told him during one thousand and one nights. Pricked by curiosity – the Sultan put off his wife’s execution from day to day, and at last gave up entirely his bloody plan.

“Many marvels were told Schahriar by the Sultana Scheherazade. For her stories the Sultana borrowed from poets their verses, from folks songs their words; and she strung together tales and adventures.

No composer has been as communicative as Rimsky-Korsakov in informing us of his aims and achievements. In his autobiography, My Musical Life, he has much to say about Scheherazade.

“The program I had been guided by in composing Scheherazade,” he writes, “consisted of separate, unconnected episodes and pictures from The Arabian Nights, scattered through all four movements of my suite: the sea and Sinbad’s ship, the fantastic narrative of the Prince Kalendar, the Prince and the Princess, the Bagdad festival and the ship dashing against the rock with the bronze rider upon it. The unifying thread consisted of the brief introductions to Movements I, II and IV and the intermezzo in Movement III, written for violin solo and delineating Scheherazade herself as telling her wondrous tales to the stern sultan. The final conclusion of Movement IV serves the same artistic purpose. In vain do people seek, in my suite, leading motives linked unbrokenly with ever the same poetic ideas and conceptions. On the contrary, in the majority of cases, all these seeming leis-motives are nothing but purely musical material or the given motives for symphonic development. These given motives thread and spread over all the movements of the suite, alternating and intertwining each with the other. Appearing as they do each time under different illumination, depicting each time different traits and expressing different moods, the self-same given motives and themes correspond each time to different images, actions and pictures. Thus, for instance, the sharply outlined fanfare motive of the muted trombone and trumpet, which first appears in the Kalender’s Narrative (Movement II) appears afresh in Movement IV, in the delineation of the wrecking ship, though this episode has no connection with the Kalender’s Narrative. The principal theme of the Kalender’s Narrative (B minor, 3/4) and the theme of the Princess in Movement III (B fiat major, 6/8, clarinet) in altered guise and quick tempo appear as the secondary themes of the Bagdad festival; yet nothing is said in The Arabian Nights about these persons taking part in the festivities. The unison phrase, as though depicting Scheherazade’s stern spouse, at the beginning of the suite appears as a datum, in the Kalendar’s Narrative, where there cannot, however, be any mention of Sultan Schahriar. In this manner, developing quite freely the musical data taken as a basis of the composition, I had in view the creation of an orchestral suite in four movements, closely knit by the community of its themes and motives, yet presenting, as it were, a kaleidoscope of fairytale images and designs of oriental character . . . Originally I had even intended to label Movement I of Scheherazade – Prelude; – Ballade; III – Adagio; and IV – Finale; but on the advice of Liadov and others I had not done so. My aversion for the seeking of a too definite program in my composition led me subsequently (in the new edition) to do away with even those hints of it which had lain in the headings of each movement, like: The Sea; Sinbad’s Ship; the Kalendar’s Narrative, etc.

“In composing Scheherazade I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had travelled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions to the will and mood of each. All I had desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic musk, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements. Why then, if that be the case, does my suite bear the name, precisely, of Scheherazade? Because this name and the title The Arabian Nights connote in everybody’s mind the East and fairytale wonders; besides, certain details of the musical exposition hint at the fact that all of these are various tales of some one person (which happens to be Scheherazade) entertaining therewith her stern husband.

Notes by PAUL AFFELDER

Label: Hallmark HM 512