Sleeve Notes:

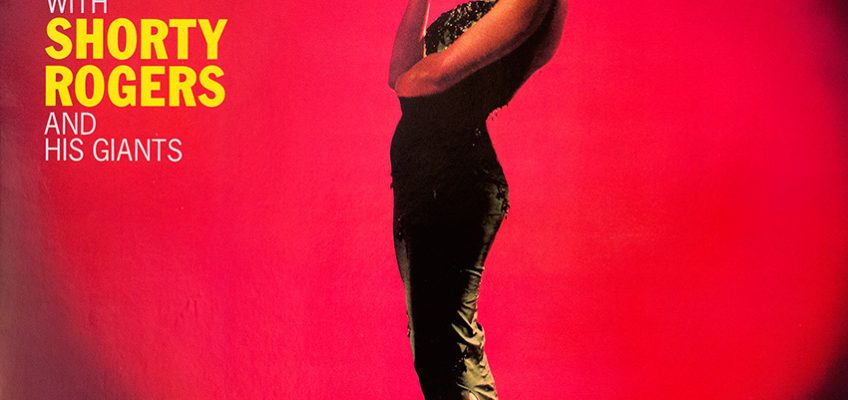

ST. LOUIS BLUES, the motion picture, is a new notch on Eartha Kitt’s achievement tree – her first Hollywood dramatic part. ST. LOUIS BLUES, the record album, scales a new promontory in her variegated recording career, presenting primarily as a blues singer an artist mainly known as the purveyor of sophisticated, mink-lined lyrics.

The material in this album, though uniformly credited to W. C. Handy, is not all strictly blues; nor is all of it to be heard in the movie, though most of the songs have at least some exposure by Eartha or one of the other artists. The details of their origin have been documented in a book of text and music, A Treasury of the Blues (Charles Boni), edited by Mr. Handy with an historical and critical analysis by Abbe Niles; comments from this book are quoted below.

The Memphis Blues, the song that pointed to Handy’s destiny, was the first blues ever documented and published. In 1909 there were three candidates for mayor of Memphis and three leading Negro bands in town. Handy, hired to play for candidate E. H. Crump, decided to celebrate the event with a new song, based on the blues form that had long been at the back of his mind. The Memphis public sang and danced in the streets to the melody of Mr. Crump; Crump was elected and Handy was lionized. The melody (there were no lyrics at that time except for a since-abandoned 16-bar middle strain) lay dormant until 1912, when a local department store worker took the manuscript, re-titled it The Memphis Blues (“better known as Mr. Crump as played by Handy & His Band,” said the sheet music cover), printed 2000 copies and put half of them in the store window. Handy, told that only 1000 copies were printed, was convinced that the piece was too hard for the public and surrendered his copyright to a selling agent for $50. Not until the statutory 28-year first-copyright period had expired was Handy able to reclaim his first hit song. Eartha’s version is the one now most often used, in which lyrics were added that speak of Handy in the third person and describe the impact of his hand on the Memphis public; George Norton of Melancholy Baby fame wrote these words. Shorty Rogers has the instrumental solo; Eartha’s concluding high note is a delightful shocker.

Careless Love, which Eartha does with Nat Cole in the picture, has a traditional, non-blues 16-bar melody that Handy recalls having heard in Bessemer, Alabama, as far back as 1892. He published it in 1921 as Loveless Love; four years later came the present version, with “additional words by Martha E. Koenig and Spencer Williams,” three stanzas of which Eartha offers.

Atlanta Blues is named for the city where Handy made headlines in 1916. His band drew 7000 to an auditorium better known for its visits from the Metropolitan Opera company. Equally well known as Make Me One Pallet on Your Floor, it was published by Handy in 1924, the composer credit being shared with Dave Elman (“known to Americans through his Hobby Lobby broad-cast,” insists the sheet music). This one, too, has a 16-bar main strain, to which Eartha adheres faithfully, as do trombonist Moe Schneider and trumpeter John Best in their solos.

In Beale Street Blues (1916) Handy recaptured some of the turbulence of the Memphis town that was later to honor him with a W. C. Handy Theatre and a Handy Park. Eartha trades lines joyously with the vocal group; the punch line refers, of course, to Prohibition’s emasculating effect on the sinful street. Gilda Gray, one of the earliest white artists to acknowledge the blues, helped make Beale Street famous.

Yellow Dog Blues (1914), which Eartha sings in the movie, has three 12-bar themes, the last taking the lyrical form of a letter from the “easy rider” to his gal (“Dear Sue .. .”). The key line, “tie’s gone where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog,” refers to two railroad lines, the Southern and the Yazoo Delta, which intersected at Morehead, Mississippi. “On the hog” means broke, and “vamp it” is a synonym for “walk it.”

Friendless Blues, ironically, was selected for the picture to be sung by Eartha as an illustration of an inadequate song, before her discovery of Handy’s music. Nevertheless, Handy did write it, in 1926, and Eartha found it so far from inadequate that she insisted on including it in the album.

Hesitating Blues, often mislabeled Hesitation, was published by Handy in 1915 and sung soon after by Blossom Seeley. Handy once credited the style of the chorus to the improvisations of a blind pianist at Mulcahy’s saloon in Memphis.

The delightful Long Gone (1920), is the true life story of a jail trusty in Bowling Green, Kentucky, who contrived an ingenious escape. Chris Smith, who wrote Bailin’ the Jack, was Handy’s collaborator. “I was happy to sing this,” says Eartha, “because I remember hearing Willie Bryant do it with his band, when I was a kid.”

Chantez-les bas (Sing ’em Low), according to Abbe Niles, “is in the Arcadian French patois with which a soft-voiced neighbor asked some of Handy’s men to please pipe down while they were serenading a girl in a Louisiana town.” As was usual with Handy, there are three different strains. and as is Eartha’s wont through. out these sides, the melodies are adhered to loyally while the Kitt personality effects a perfect merger with them. One of Handy’s later publications (1931), it is sung by Eartha in the dramatic film sequence that reveals his incipient blindness.

St. Louis Blues (1914) is Handy’s monument, the most famous blues in the world. Nat Cole and Eartha sing it in the film, in a version strikingly different from that heard here. Matty Matlock’s arrangement keeps a suggestion in the opening chorus of the tango rhythm that was a revolutionary novelty when the song was first performed. Eartha, by being herself and allowing the melody to be itself, offers one of the most genuine interpretations of the five hundred recorded in the song’s forty-four years of life.

St. Louis Blues (1914) is Handy’s monument, the most famous blues in the world. Nat Cole and Eartha sing it in the film, in a version strikingly different from that heard here. Matty Matlock’s arrangement keeps a suggestion in the opening chorus of the tango rhythm that was a revolutionary novelty when the song was first performed. Eartha, by being herself and allowing the melody to be itself, offers one of the most genuine interpretations of the five hundred recorded in the song’s forty-four years of life.

Steal Away and Hist the Window, Noah, both Handy spiritual adaptations and both sung in the picture by Mahalia Jackson, offer us a chance to hear a different Eartha. “I sang these purely with chest tones,” she says; “all the other songs are done mainly with head tones. I’ve always wanted to do Negro spirituals and we thought it would be a fine idea for contrast to include a couple of them in the album.”

The arrangements by Julian “Matty” Matlock, 49-year-old clarinet veteran from Paducah, Kentucky, and alumnus of the Ben Pollack, Bob Crosby and Red Nichols bands, are in perfect keeping with the spirit of the album and of Handy’s music. I suspect that this album will spend many hours on Mr. Handy’s own turntable. For once, a set of his works has been performed, arranged and sung with the same loving care and fidelity that would be accorded them by the composer himself.

LEONARD FEATHER © by Radio Corporation of America, 1958

Jester Hairston arranged Steal Away and Hist the Window, Noah, and it is his choir that accompanies Miss Kitt on those selections. The arrangements for all the other numbers were made by Matty Matlock, and Miss Kitt was backed by the following people: SHORTY ROGERS—Leader and Trumpet JOHN BEST—Trumpet MOE SCHNEIDER—Trombone MATTY MATLOCK—Clarinet STAN WRIGHTSMAN—Piano AL HENDRICKSON—Guitar MORTY CORB—Bass NICK FATOOL—Drums MILT HOLLAND—Conga Drums

EARTHA KITT With Shorty Rogers and his Orchestra ® 1958 RCA RECORDS

Label: RCA NL 89436

1958 1950s Covers (1984 reissue)