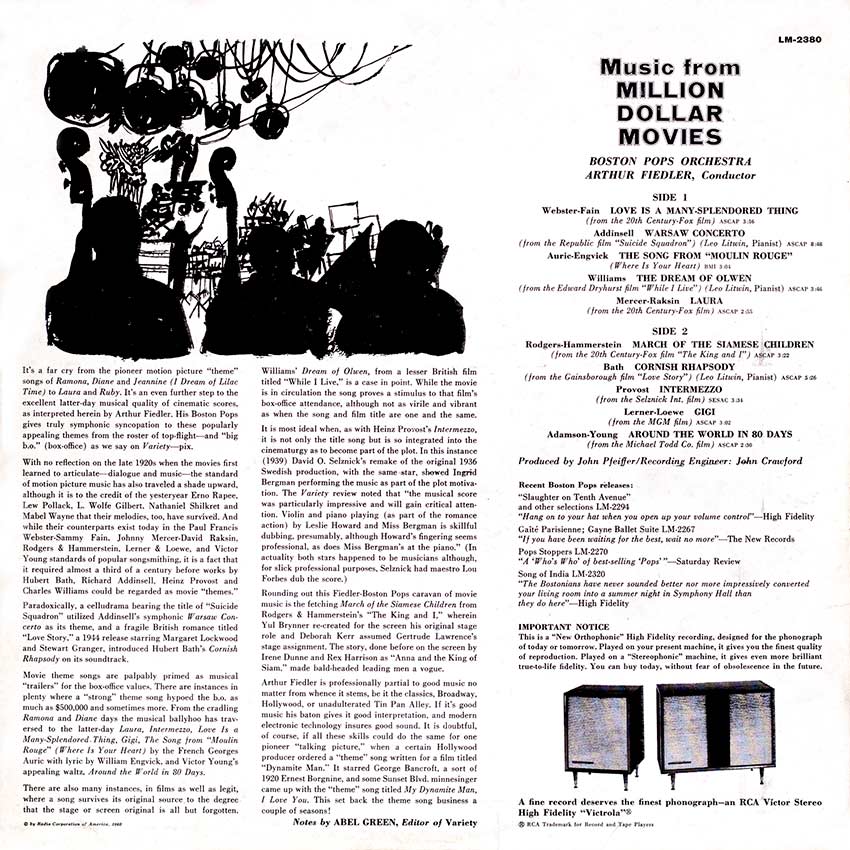

Sleeve Notes:

It’s a far cry from the pioneer motion picture “theme” songs of Ramona, Diane and Jeannine (I Dream of Lilac Time) to Laura and Ruby. It’s an even further step to the excellent latter-day musical quality of cinematic scores, as interpreted herein by Arthur Fiedler. His Boston Pops gives truly symphonic syncopation to these popularly appealing themes from the roster of top-flight and “big b.o.” (box-office) as we say on Variety pix.

Paradoxically, a celludrama bearing the title of “Suicide Squadron” utilized Addinsell’s symphonic Warsaw Concerto as its theme, and a fragile British romance titled “Love Story,” a 1944 release starring Margaret Lockwood and Stewart Granger, introduced Hubert Bath’s Cornish Rhapsody on its soundtrack.

Movie theme songs are palpably primed as musical “trailers” for the box-office values. There are instances in plenty where a “strong” theme song hypoed the b.o. as much as $500,000 and sometimes more. From the cradling Ramona and Diane days the musical ballyhoo has traversed to the latter-day Laura, Intermezzo, Love Is a Many Splendored Thing, Gigi, The Song from “Moulin Rouge” ( Where Is Your Heart) by the French Georges Auric with lyric by William Engvick, and Victor Young’s appealing waltz, Around the World in 80 Days.

There are also many instances, in films as well as legit, where a song survives its original source, to the degree that the stage or screen original is all but forgotten. Williams’ Dream of Olwen, from a lesser British film titled “While I Live,” is a case in point. While the movie is in circulation the song proves a stimulus to that film’s box-office attendance, although not as virile and vibrant as when the song and film title are one and the same.

It is most ideal when, as with Heinz Provost’s Intermezzo, it is not only the title song but is so integrated into the cinematurgy as to become part of the plot. In this instance (1939) David O. Selznick’s remake of the original 1936 Swedish production, with the same star, showed Ingrid Bergman performing the music as part of the plot motivation. The Variety review noted that “the musical score was particularly impressive and will gain critical attention. Violin and piano playing (as part of the romance action) by Leslie Howard and Miss Bergman is skillful dubbing, presumably, although Howard’s fingering seems professional, as does Miss Bergman’s at the piano.” (In actuality both stars happened to be musicians although, for slick professional purposes, Selznick had maestro Lou Forbes dub the score.)

Rounding out this Fiedler-Boston Pops caravan of movie music is the fetching March of the Siamese Children from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “The King and I,” wherein Yul Brynner re-created for the screen his original stage role and Deborah Kerr assumed Gertrude Lawrence’s stage assignment. The story, done before on the screen by Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison as “Anna and the King of Siam,” made bald-headed leading men a vogue.

Arthur Fiedler is professionally partial to good music no matter from whence it stems, be it the classics, Broadway, Hollywood, or unadulterated Tin Pan Alley. If it’s good music his baton gives it good interpretation, and modern electronic technology insures good sound. It is doubtful, of course, if all these skills could is the same for one pioneer “talking picture,” when a certain Hollywood producer ordered a “theme” song written for a film titled “Dynamite Man.” It starred George Bancroft, a sort of 1920 Ernest Borgnine, and some Sunset Blvd. minnesinger came up with the “theme” song titled My Dynamite Man, I Love You. This set back the theme song business a couple of seasons!

Notes by ABEL GREEN, Editor of Variety

Label: RCA LM-2380