Sleeve Notes:

SIDE ONE

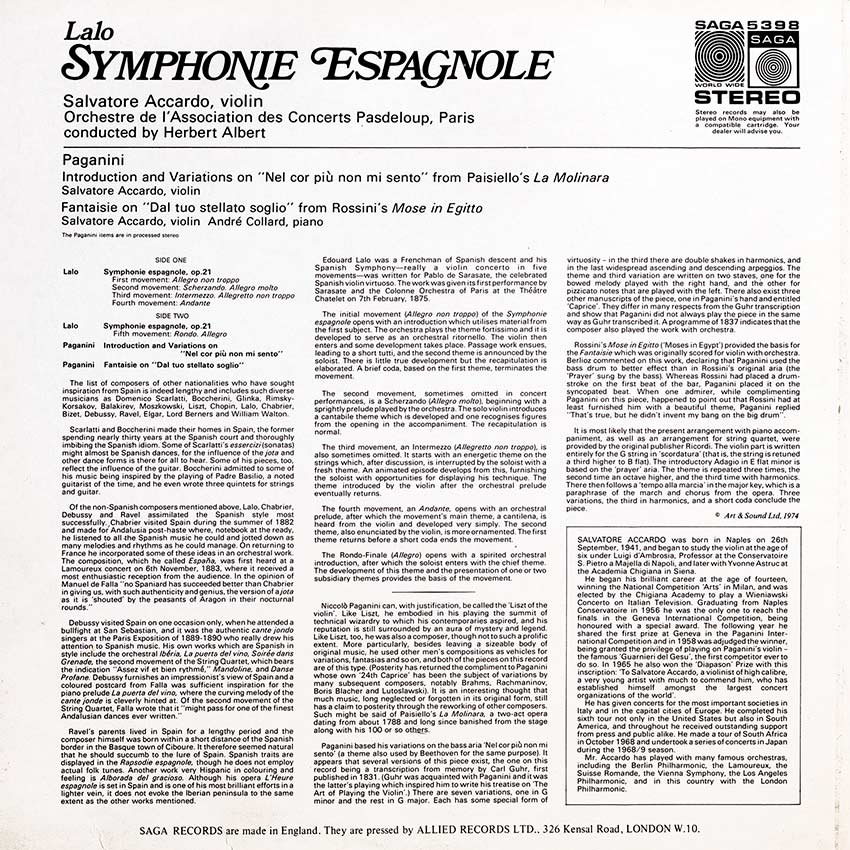

Lalo Symphonie espagnole, op.21 First movement: Allegro non troppo Second movement: Scherzando. Allegro molto Third movement: Intermezzo. Allegretto non troppo Fourth movement: Andante

SIDE TWO Lalo Symphonie espagnole, op.21 Fifth movement: Rondo. Allegro Paganini Introduction and Variations on “Nel cor piu non mi sento” Paganini Fantaisie on “Dal tuo stellato soglio”

Scarlatti and Boccherini made their homes in Spain, the former spending nearly thirty years at the Spanish court and thoroughly imbibing the Spanish idiom. Some of Scarlatti’s essercizi (sonatas) might almost be Spanish dances, for the influence of the jota and other dance forms is there for all to hear. Some of his pieces, too, reflect the influence of the guitar. Boccherini admitted to some of his music being inspired by the playing of Padre Basilio, a noted guitarist of the time, and he even wrote three quintets for strings and guitar.

Of the non-Spanish composers mentioned above, Lalo, Chabrier, Debussy and Ravel assimilated the Spanish style most successfully, Chabrier visited Spain during the summer of 1882 and made for Andalusia post-haste where, notebook at the ready, he listened to all the Spanish music he could and jotted down as many melodies and rhythms as he could manage. On returning to France he incorporated some of these ideas in an orchestral work. The composition, which he called Espana, was first heard at a Lamoureux concert on 6th November, 1883, where it received a most enthusiastic reception from the audience. In the opinion of Manuel de Falla “no Spaniard has succeeded better than Chabrier in giving us, with such authenticity and genius, the version of a jota as it is ‘shouted’ by the peasants of Aragon in their nocturnal rounds.”

Debussy visited Spain on one occasion only, when he attended a bullfight at San Sebastian, and it was the authentic cante jondo singers at the Paris Exposition of 1889-1890 who really drew his attention to Spanish music. His own works which are Spanish in style include the orchestral Iberia, La puerta del vino, Soiree dans Grenade, the second movement of the String Quartet, which bears the indication “Assez vif et bien rythme,” Mandoline, and Danse Profane. Debussy furnishes an impressionist’s view of Spain and a coloured postcard from Falla was sufficient inspiration for the piano prelude La puerta del vino, where the curving melody of the cante jonde is cleverly hinted at. Of the second movement of the String Quartet, Falla wrote that it “might pass for one of the finest Andalusian dances ever written.”

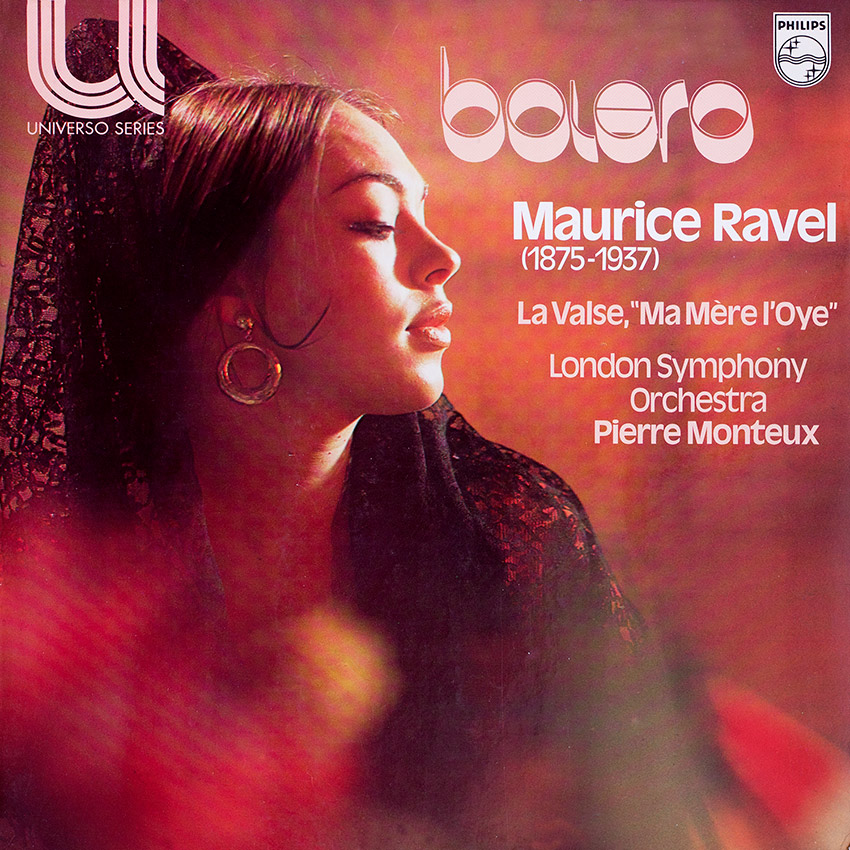

Ravel’s parents lived in Spain for a lengthy period and the composer himself was born within a short distance of the Spanish border in the Basque town of Ciboure. It therefore seemed natural that he should succumb to the lure of Spain. Spanish traits are displayed in the Rapsodie espagnole, though he does not employ actual folk tunes. Another work very Hispanic in colouring and feeling is Alborada del gracioso. Although his opera L’Heure espagnole is set in Spain and is one of his most brilliant efforts in a lighter vein, it does not evoke the Iberian peninsula to the same extent as the other works mentioned.

Edouard Lalo was a Frenchman of Spanish descent and his Spanish Symphony – really a violin concerto in five movements – was written for Pablo de Sarasate, the celebrated Spanish violin virtuoso. The work was given its first performance by Sarasate and the Colonne Orchestra of Paris at the Theatre Chatelet on 7th February, 1875.

The initial movement (Allegro non troppo) of the Symphonic espagnole opens with an introduction which utilises material from the first subject. The orchestra plays the theme fortissimo and it is developed to serve as an orchestral ritornello. The violin then enters and some development takes place. Passage work ensues, leading to a short tutti, and the second theme is announced by the soloist. There is little true development but the recapitulation is elaborated. A brief coda, based on the first theme, terminates the movement.

The second movement, sometimes omitted in concert performances, is a Scherzando (Allegro molto), beginning with a sprightly prelude played by the orchestra. The solo violin introduces a cantabile theme which is developed and one recognises figures from the opening in the accompaniment. The recapitulation is normal.

The third movement, an Intermezzo (Allegretto non troppo), is also sometimes omitted. It starts with an energetic theme on the strings which, after discussion, is interrupted by the soloist with a fresh theme. An animated episode develops from this, furnishing the soloist with opportunities for displaying his technique. The theme introduced by the violin after the orchestral prelude eventually returns.

The fourth movement, an Andante, opens with an orchestral prelude, after which the movement’s main theme, a cantilena, is heard from the violin and developed very simply. The second theme, also enunciated by the violin, is more ornamented. The first theme returns before a short coda ends the movement.

The Rondo-Finale (Allegro) opens with a spirited orchestral introduction, after which the soloist enters with the chief theme. The development of this theme and the presentation of one or two subsidiary themes provides the basis of the movement.

Niccolo Paganini can, with justification, be called the ‘Liszt of the violin’. Like Liszt, he embodied in his playing the summit of technical wizardry to which his contemporaries aspired, and his reputation is still surrounded by an aura of mystery and legend. Like Liszt, too, he was also a composer, though not to such a prolific extent. More particularly, besides leaving a sizeable body of original music, he used other men’s compositions as vehicles for variations, fantasias and so on, and both of the pieces on this record are of this type. (Posterity has returned the compliment to Paganini whose own ’24th Caprice’ has been the subject of variations by many subsequent composers, notably Brahms, Rachmaninov, Boris Blacher and Lutoslawski). It is an interesting thought that much music, long neglected or forgotten in its original form, still has a claim to posterity through the reworking of other composers. Such might be said of Paisiello’s La Molinara, a two-act opera dating from about 1788 and long since banished from the stage along with his 100 or so others. Paganini based his variations on the bass aria ‘Nel cor pib non mi sento’ (a theme also used by Beethoven for the same purpose). It appears that several versions of this piece exist, the one on this record being a transcription from memory by Carl Guhr, first published in 1831. (Guhr was acquainted with Paganini and it was the latter’s playing which inspired him to write his treatise on ‘The Art of Playing the Violin’.) There are seven variations, one in G minor and the rest in G major. Each has some special form of virtuosity – in the third there are double shakes in harmonics, and in the last widespread ascending and descending arpeggios. The theme and third variation are written on two staves, one for the bowed melody played with the right hand, and the other for pizzicato notes that are played with the left. There also exist three other manuscripts of the piece, one in Paganini’s hand and entitled ‘Caprice’. They differ in many respects from the Guhr transcription and show that Paganini did not always play the piece in the same way as Guhr transcribed it. A programme of 1837 indicates that the composer also played the work with orchestra.

Rossini’s Mose in Egitto (‘Moses in Egypt’) provided the basis for the Fantaisie which was originally scored for violin with orchestra. Berlioz commented on this work, declaring that Paganini used the bass drum to better effect than in Rossini’s original aria (the ‘Prayer’ sung by the bass). Whereas Rossini had placed a drum-stroke on the first beat of the bar, Paganini placed it on the syncopated beat. When one admirer, while complimenting Paganini on this piece, happened to point out that Rossini had at least furnished him with a beautiful theme, Paganini replied “That’s true, but he didn’t invent my bang on the big drum”.

It is most likely that the present arrangement with piano accompaniment, as well as an arrangement for string quartet, were provided by the original publisher Ricordi. The violin part is written entirely for the G string in ‘scordatura’ (that is, the string is retuned a third higher to B flat). The introductory Adagio in E flat minor is based on the ‘prayer’ aria. The theme is repeated three times, the second time an octave higher, and the third time with harmonics. There then follows a ‘tempo alla marcia’ in the major key, which is a paraphrase of the march and chorus from the opera. Three variations, the third in harmonics, and a short coda conclude the piece.

© Art &Sound Ltd, 1974

SALVATORE ACCARDO was born in Naples on 26th September, 1941, and began to study the violin at the age of six under Luigi d’Ambrosia, Professor at the Conservatoire S. Pietro a Majella di Napoli, and later with Yvonne Astruc at the Academia Chigiana in Siena. He began his brilliant career at the age of fourteen, winning the National Competition ‘Arts’ in Milan, and was elected by the Chigiana Academy to play a Wieniawski Concerto on Italian Television. Graduating from Naples Conservatoire in 1956 he was the only one to reach the finals in the Geneva International Competition, being honoured with a special award. The following year he shared the first prize at Geneva in the Paganini Inter-national Competition and in 1958 was adjudged the winner, being granted the privilege of playing on Paganini’s violin -the famous ‘Guarnieri del Gesu’, the first competitor ever to do so. In 1965 he also won the ‘Diapason’ Prize with this inscription: ‘To Salvatore Accardo, a violinist of high calibre, a very young artist with much to commend him, who has established himself amongst the largest concert organizations of the world’. He has given concerts for the most important societies in Italy and in the capital cities of Europe. He completed his sixth tour not only in the United States but also in South America, and throughout he received outstanding support from press and public alike. He made a tour of South Africa in October 1968 and undertook a series of concerts in Japan during the 1968/9 season. Mr. Accardo has played with many famous orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, the Lamoureux, the Suisse Romande, the Vienna Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and in this country with the London Philharmonic.

Label: Saga 5398