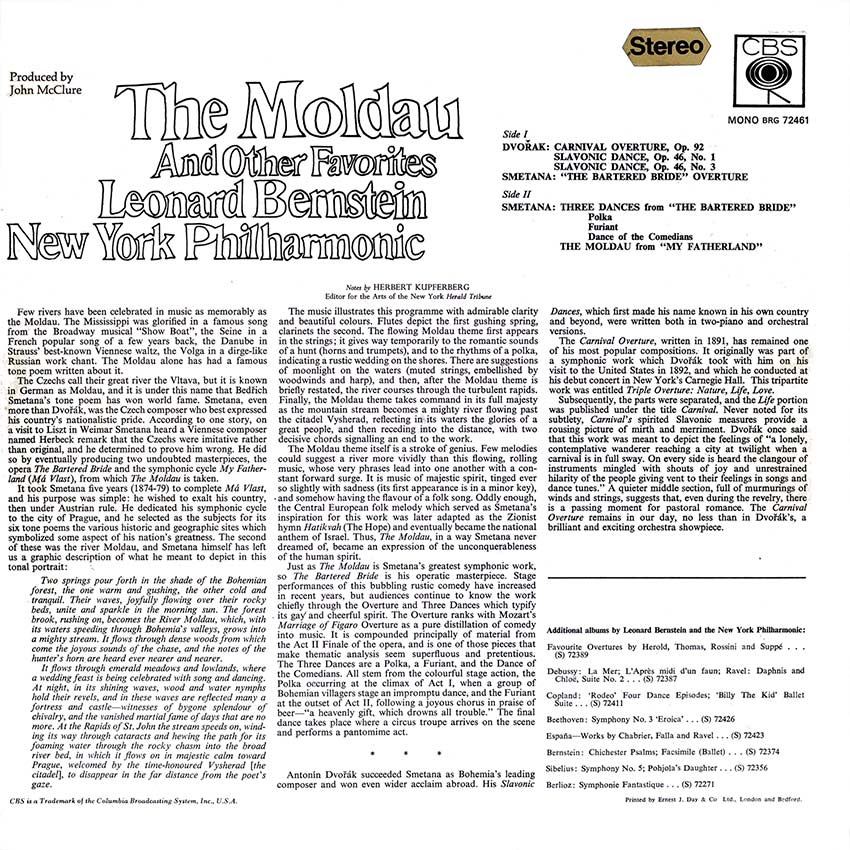

It is no novelty to be told that such and such generally acknowledged musical masterpiece failed miserably to please the audience at its first performance. However, not all these initial failures resulted from the music’s being too far in advance of its listeners, or even too far removed from their general aesthetic atmosphere.

A good many pieces failed, at first, for reasons having nothing to do with the composition in question, and some failed for reasons having nothing at all to do with music. The three pieces on this record, whose destinies were rather curiously intertwined, are peculiarly in the latter group. But it should be emphasized that what we are discussing here is the public reaction, not that of the professional critics. Claude Debussy’s

La Mer is a case in point. After its first performance, under the direction of Camille Chevillard at the Concerts Lamoureux in Paris, the critics ex-pressed dissatisfaction for widely divergent reasons. Some apparently had glanced at their scores (or program notes), noted the titles of

La Mer’s three movements (“From Dawn to Noon on the Sea,” “Play of the Waves,” “Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea”) and prepared themselves for some kind of wave-by-wave program music. They were quick to reveal disappointment over the music’s being evocative rather than explicit. Among them, perhaps, could be placed the shyly ironic figure of Erik Satie who, in commenting on “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea,” acknowledged that he particularly liked the little bit at a quarter to eleven. Other critics, on the contrary, such as Pierre Lalo, had anticipated a further development of the understated musical description which, particularly in

Pelleas et Melisande, had helped to establish Debussy’s musical reputation. The com-plaint of these critics was that

La Mer seemed too explicit—and, at the same time, too symphonic. Lalo intimated that the entire composition could not compare in impact to the grotto scene in

Pelleas, “where only a few chords and a single orchestral rhythm gave the atmosphere of night and of the sea. . . . ” If the critics had varying and contradictory reasons for dis-liking

La Mer, the Parisian audiences paid no attention to all the fuss in the press and cut right through to the heart of the matter—Debussy himself. It was not

La Mer at all that was the focus of the public’s scathing attention, but Debussy’s private life over the three years in which he composed the work. In those three years, the composer had matter-of-factly proceeded to discard his first wife, Lily Texier, in favour of his second, Emma Bardac. Lily was a simple, beautiful, provincial girl who had been totally devoted to Debussy for the five years of their marriage. Emma Bardac was wealthy and worldly—already a wife and the mother of grown children.

It was not difficult to predict which of the two women would have the public’s sympathies in such an affair, and sympathy for Lily became outrage at Debussy’s behaviour when he not only failed to be visibly moved by Lily’s almost-successful attempt at suicide, but barely managed to spare a few minutes to visit her in the hospital on the way to join Emma Bardac. By the time of La Mer’s first performance, Debussy’s private affairs had become public property. They were to become even more so a few weeks later with the appearance of a play, La Femme nue, by Henri Bataille, which was a superbly written and undisguised account of Debussy’s life with Lily. Paris showed its anger at Debussy by greeting La Mer in the worst way it knew how—with an icy silence that hardly acknowledged the work’s existence. And while the critics began to recognize the unmistakable merits of “Debussy’s symphony” within a few weeks of its premiere, it was many years before the music’s stature with the public transcended the circumstances of its first performance. But a frigid silence is hardly a typical Parisian reaction, or even a typical Parisian negative reaction. Much more in keeping with the historical hot tempers of French audiences was the reception afforded a few years later, to the first performance of the ballet L’ Apres-midi d’un faune. It immediately became the subject of fiery controversy, and this time the audience was reacting neither to Debussy’s music nor to his private life. The Prelude a l’ Apres-midi d’un faune, Debussy’s musical interpretation of Stephane Mallarme’s famous poem, had grown musically successful since 1894, when it was per-formed at the Salle d’Harcourt and described by one irate critic as music for a pack of headhunters. In a terse preface to the score, Debussy said, “It evokes the successive echoes of the faun’s desires and dreams on a hot afternoon.” At its premiere as a ballet in 1912, under the aegis of Diaghilev, Nijinsky and the Ballet Russe, L’ Apres-midi evidently did much more than “evoke.” It became an instant and total scandal, with headlines screaming across newspaper front pages, editorials attacking and defending, and men and women insulting each other whenever the subject was brought up. Both the source and the nature of the controversy was made most explicit by Gaston Calmette, editor of Le Figaro, who suppressed a mildly disapproving review of the ballet in favour of his own far more pointed comment. His famous editorial, “Un Faux pas,” ended : “. . Those who speak of art and poetry apropos this spectacle mock us. It is neither a graceful eclogue nor a serious production. We saw a faun, incontinent, vile—his gestures those of erotic bestiality and shamelessness. That is all. And well-deserved boos greeted this too-expressive pantomime of the body of an ill-made beast, hideous from the front, even more hideous in profile. These animal realisms never will be acceptable.” It goes without saying that the “animal realisms” eventually proved inoffensive enough. In the meantime, the ballet was anything but harmed by the intense controversy, for an eager audience awaited every performance. Ironically, the only real harm done by L’affaire de “L’ Apres-midi” was to Ravel. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe was unquestionably one of the most potent catalysts of all time on artistic activity. Among the first artists attracted by the Ballet on its arrival in Paris in 1901 was Maurice Ravel. Ravel already had come to know Diaghilev through the composer’s attempts to persuade him to stage a full-length production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov during the impresario’s presentation of Russian works at the Paris Opera. Although Ravel failed to make Diaghilev share -his appreciation of Mussorgsky, he left unmistakable evidence of his own talents, and the com-poser was a welcome observer at the Ballet Russe’s rehearsals for their first Paris season. Like almost everyone present at those rehearsals, Ravel was intoxicated by the headlong verve with which the entire troupe seemed to behave. And when he began to compose the score of Daphnis et Chloe, he did so with the memory of the Ballet’s incredible debut—and Nijinsky’s legendary leaps—fresh in his mind. But for all of Ravel’s enthusiasm, and the respect in which he was held by the troupe, difficulties in mounting the ballet arose from the start. For one thing, Ravel’s conception of the ancient Greece against which Daphnis et Chloe should be set was not the same as that of Fokine, the choreographer, and Bakst, the stage designer. For another, the eventual estrangement of Fokine and Diaghilev was predictable be-cause of the increasing number of vehement arguments between the two. One reason after another postponed the staging of Daphnis et Chloe from season to season. What spoiled the eventual debut at the Theatre Chatelet in 1912, however, was not any definite artistic weakness in the production itself—but the furor over Debussy’s L’ Apres-midi, which had been given its premiere only the week before. Not only had Nijinsky’s intense preparations for the Debussy ballet (some one hundred twenty rehearsals) left little time and energy for the polishing of Daphnis et Chloe, but the intensity of the public debate over L’ Apres-midi left little energy, on their part, for any notice of Ravel’s work. While the music of Daphnis et Chloe has never been under-valued from the time of its first performance to the present, the production of the ballet, perhaps, has never been a success on the scale it might have been. Herein lies one more concrete reminder of the strange coexistence and mutual influence of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

CBS is a Trademark of the Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., U.S.A. Recorded in the U.S.A. by CBS Records, a Division of Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.